Ask any two horror fans why they’re fans in the first place expecting similar answers, and I think you’re in for some disappointment. We come to horror for as many different reasons as there are fans in the first place. But if you’ll forgive my armchair psychologizing, I think that all horror fans are, at least in part, trying to deal with some very big issues. Why do bad things happen? Why do we die? Why is there so much pain in the world? All the stuff that sneaks right up to the really big questions that are buried in our noggin and then for some reason brings us to screens to watch people get run through a meat grinder. I’m not sure what the mechanism is that makes that useful, but I do know that from time to time, we have to wallow in the bleakness, you know? And I think that people often come to spaghetti westerns for similar reasons. American westerns are mostly morality stories where the good guys win and the bad guys get what’s coming to them. The Italians, just a couple of decades after the horrors of being on the wrong side of a world war and actual fascism were less sanguine in their approach to the genre, and their versions of the western were often more violent, ugly and considerably more amoral. In that way, the spaghetti western was probably more akin to the horror film than to the American western. The spaghetti western was rarely looking to offer a tense yet ultimately comfortable reassurance to its audiences. Instead, like the horror film, they were trying to touch on some very basic but difficult questions and examine them up close.

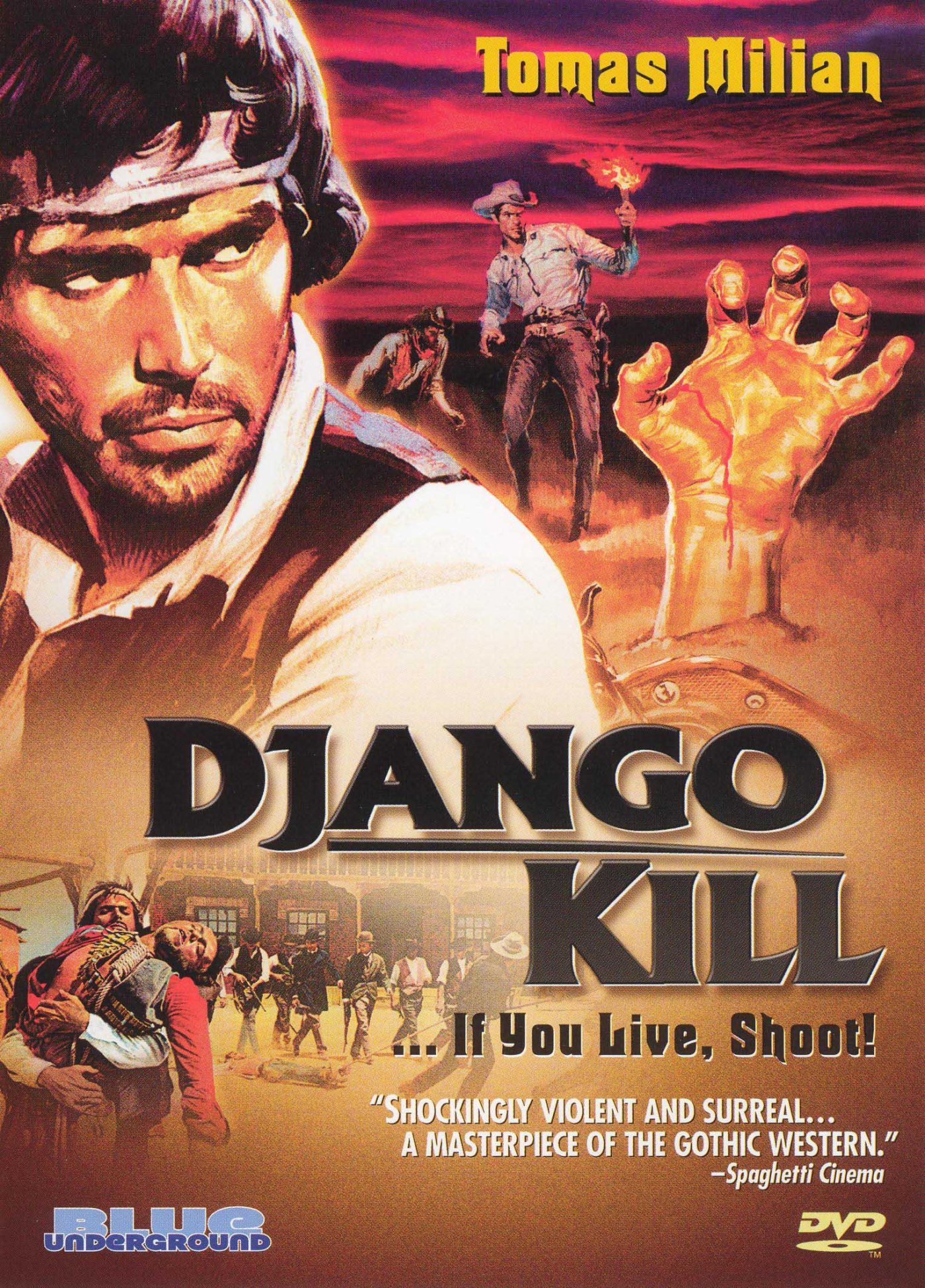

But even in this subgenre known for its bleakness, amorality and viciousness, there are some that stand out as examples that shock even the most hardened viewer. Cut Throats Nine (1972) shocks the viewer with the depths of its depravity and the absolute callousness with which it snuffs out human life. The Great Silence (1968) is truly one of the bleakest films ever made, a film where no good deed goes horrifically unpunished. Four of the Apocalypse (1975) is Fulci making a western with Jodorowsky levels of weirdness. To that list, we would have to add in Django Kill… If You Live, Shoot! (1967) which I would say gives Cut Throats Nine a run for its money as the most notoriously violent western ever made.

Virtually every person in this film is gigantically avaricious, wildly violent, viciously self-centered, criminally insane and/or generally awful. Tomas Milan plays The Stranger who is also Django, I guess? He’s never called anything but The Stranger, but the film has Django in the title and he’s the main character, so I guess he’s Django. Anyway, to give you a feel for where this movie is headed, the first shots are of him, barely alive, clawing and squalling his way out of a mass grave. He is discovered by two “natives” (Miguel Serrano and Angel Silva) who set about the task of nursing him back to life. Within the first three minutes of the film we are treated to one of co-writer and editor Franco “Kim” Arcalli’s wild editing montages. This one’s a real dialectical humdinger that bounces back and forth between shots of the Stranger lying near death in the dark and glimpses of a scene of him being shot along with several other men in the sun-seared daylight. There is an economy in this editing style that conveys a really stark feeling in a handful of seconds, juxtaposing the present with the past, the shooting and the consequences of the shooting. It’s a trope of the western to see a character die dramatically after a single gunshot, and so a character suffering horribly from the lingering effects of several gunshots is a pretty bracing divergence from what you’d expect from the genre. Another montage comes close behind that one, this time of people being shot and a bag of gold cut open. This film has a lot going for it, but one of its strongest points (for fans of such things) is the editing. This is a film that occasionally draws attention to the cuts and uses them to create the feelings of ugliness and dread that pervade the film. Armchair and professional pundits alike might draw attention to that and call it sloppy filmmaking, but I have come to strongly disagree. Much like how Van Gogh made the brush strokes a living part of the painting, the artifice of filmmaking creeping into the film itself can add texture and details as well as subtext. I think seeing these brushstrokes can remind you of the artifice and also remind you that it was created for a reason. They you can ask yourself why.

In the ten minutes that follow the opening montage-a-thon we are shown the events that led The Stranger to be doctored by shamans on the edge of his own grave. Were this an American western, this sequence would probably be about him having been a farmer attacked by soldiers or the father of a family in a wagon train attacked by (probably, cringe) “Indians” but not for this film. See, The Stranger and his eventual would-be assassins all snuck up on a wagon full of gold dust being guarded by a platoon of soldiers. Soldiers who weren’t standing at arms, but instead were clowning in a river, defenses down to zero. The Stranger and his buddies straight up murder most of them; shot in the back or running away, in cold blood. The ambush group is made up of two ethnic tribes: one, all-Caucasian and led by the ever-grinning Oaks (Piero Lulli) and the other all-Mexican led by our “half-breed” protagonist the Stranger. As they are loading up the gold, and in classic mustache-twirling fashion, Oaks explains that he doesn’t feel like sharing any of it with a “bunch of motherless Mexicans.” The Mexicans are apparently so taken aback by the dichotomy of being called “motherless” while their existence clearly offers evidence for the fact of their mothers, that they are taken hostage and forced to dig their own grave by the armed white men. This sequence introduces the white guys in the gang, who sneer and laugh and generally express some of the most punchable faces in the history of European cinema. This very much feels like director Giulio Questi is setting up this band as the film’s antagonists, and it works, as I wanted to see each of them skinned and fed to centipedes. But can we talk for a minute about the guys digging their own graves? This is a film trope that drives me goddamned bananas. I’m sure it’s true that the mind has a hard time actually believing that someone is planning to kill you, and assumes that if you play along with whatever they ask and follow their instructions you might get out alive. However, in fiction, I want these guys to stop digging their own graves and do something. One of the doomed men apparently heard me hollering at the screen and reacted. Now I’ve never been in a situation where I was about to be executed, but I like to think that if I was, I’d at least figure out a way to make it hard on the people doing the executing. I’d prefer not to meet my maker and tell them that my final act was assisting my executioners in making my murder less of a chore for them. And so this unnamed hero either kills or drives away many of the bandit’s horses before being killed himself, setting up the main plot of the film. The rest of the motherless are lined up and gunned down, all while The Stranger is hurling threats.

This opening twelve or so minutes is very important, as it sets up the plot that you think the film will take and also sets up the (very different) plot the film actually takes. It also tells us the main motivation of the film, and it tells us important details about our protagonist. Let’s start with this last bit, because I don’t want it to get lost. Right before Oaks betrays the Stranger and his crew, the Stranger has a fairly strange (go figure) bit of dialogue where he talks about the “work” they just did together and how enjoyable he found it. It is critical to note that “the work” he is talking about was a cold, calculated and cowardly mass murder. Had we been following the story of the soldiers, The Stranger would absolutely be a villain, and based on his actions he is a villain. Further, his dialogue suggests that this is work he has enjoyed in the past. So it’s not too much to infer that he has ambushed and killed unarmed people in the past. This was a “job,” this murder most foul, and no matter what he does to redeem himself moving forward, which is nothing really, he has this permanent stain on him. In many ways, placing this man in the role of protagonist is more horrific than much of what happens in the average horror film, so why do it? Well, if you’re asking questions about why horrible things exist, you will likely have to get close to them.

The surviving white thieves quickly realize that to make their great escape, they will need horses to carry all of their punchable faces, so they make their way to the closest town they can find. From here, the film takes a series of hard left turns until the plot the audience rightly anticipates evaporates into thin air and something new and even more sinister becomes the main course. Because it would spoil much of what’s really cool about the film, I don’t want to go too much into what happens next, but I will say one thing: if you can, watch the Blue Underground release that includes the scene of Oaks being tended to by a doctor while laying on a table. All the American releases cut this sequence absurdly and in the versions available online, the scene makes makes no sense. But it is brutal and deserves your attention, not just for its brutality but because this film presents a cascading series of terrible events that function as introductions to characters and places. By doing it this way, the brutal avariciousness of people and whole populations is revealed, like some sort of rotten Russian doll where each nested layer is the same but more corrupt than the last.

This film manages to really pull out the stops in delivering the goods. Some other “highlights” include: crucifixion, torture by vampire bat, human slavery, life and death party games, and being smelted to death. It would be reasonable to ask why on earth you would want to experience this sort of thing, and the glib answer is “if you don’t get it you just don’t get it.” But I think that it’s more than that. I think that sometimes we want to be shocked. Sometimes we want to be jolted awake and be forced to look at the hard stuff, and this film does a pretty good job of being jolting. This isn’t a horror movie but it rides the same dark highway that horror rides on and for that reason, I think that the average horror fan with a taste for the dusty, hot, and merciless old west as envisioned by mid-20th century Italians would appreciate having this one in their collection. It bears revisiting until you’ve wrung out the last drop of the red stuff. And there are a LOT of drops.